Key Principles & Best Practices for Communication in Rock Climbing

Clear and reliable communication is the foundation of safety in rock climbing.

Communication failures caused by environmental interference, inconsistent terminology, or unclear intent can lead to serious consequences.

Based on professional rock climbing instruction experience, this article systematically elaborates on common communication barriers in climbing and provides practical advice for establishing robust communication strategies, aiming to help climbers enhance safety awareness and operational reliability.

I. Identifying Communication Barriers in Climbing

Communication barriers refer to any situation that causes information to be conveyed unclearly, incompletely, or interrupted. They vary in form and severity, primarily stemming from the following three core factors:

1. Environmental Interference: Loud ambient noise, such as passing vehicles, strong wind, or the sound of rushing rivers, can instantly drown out commands. Sudden weather changes can also render verbal communication entirely ineffective. Furthermore, commands can easily be confused when multiple groups of climbers are shouting simultaneously.

2.Inconsistent Terminology: Different climbers may use different words for the same command. For example, variations in how protection status is confirmed can easily lead to misunderstandings.

3.Unclear Intent: A climber failing to clearly express their intent regarding their next move can cause the belayer to fail to form correct expectations and provide proper support. An example is failing to perform a double-check communication before leading a pitch.

II. Establishing Standardized Communication Strategies

Climbing teams should avoid the dangerous assumption of “defaulting that the other party communicates the same way we do,” especially in newly formed partnerships. Establishing a unified communication strategy is crucial.

- Reach Consensus Before Starting: All members should agree on the command language and communication methods to be used while still on the ground before starting the climb.

- Resolving Disagreements: If disagreements arise over tactics or language, they must be resolved through discussion and compromise. Climbing should only begin after all members unquestionably understand the entire communication process.

III. Maintaining Clear Action Plans in Long-Term Partnerships

Even experienced, well-coordinated long-term partners can develop communication gaps due to complacency.

- Avoid Complacency Assumptions: Before every climb, proactively confirm key operational steps, avoiding assumptions.

A typical example is at the end of a single-pitch climb: should one choose to clean the route while descending after being taken off belay, or be lowered by the belayer while remaining on belay?

Even if one method is consistently used, the plan for this specific instance should be clarified beforehand.

- Follow Professional Advice: The American Alpine Club and the American Mountain Guides Association recommend prioritizing being lowered over rappelling when cleaning a single-pitch route to reduce risk.

IV. Regulated Use of Radios and Emergency Preparedness

Radios in climbing should be treated as critical safety tools, not communication toys. Responsible use requires adhering to the following protocols:

- Equipment Check: Always check battery levels and test channel and transmission functionality before use.

- Channel Management: Confirm that the selected channel is not in use by other parties; change it immediately if necessary.

- Develop a Backup Plan: Always pre-establish an emergency communication plan for a scenario where the radio system fails completely.

V. Extending Communication Strategies to Adjacent Parties

On crowded crags, an individual’s communication plan should include considerations for adjacent parties.

- Proactive Identification: Proactively introduce yourself and learn the names of nearby climbers. Using names when passing commands effectively ensures the information reaches the correct person.

- Handling Same Names: If someone in an adjacent party shares the same name, immediately agree on a way to distinguish each other (e.g., “Red-Helmet David”) to prevent command confusion.

VI. Keeping Commands Concise, Avoiding Redundant Information

Whether using radios or not, conciseness is the lifeline of communication. Redundant information dilutes focus on critical commands and increases the risk of misinterpretation.

Focus on Key Commands: Communication channels should be used for conveying essential operational information, not casual conversation.

For example, when a lead climber has built an anchor and is ready to belay, the clear command sequence should be: “Off belay” -> (After readiness is confirmed) “On belay.”

Observations about the environment, wildlife, etc., should be saved for when both parties are securely at a belay station.

Use Streamlined Language: When shouting directly, fewer words and syllables increase the likelihood of the message being received accurately in noisy environments.

VII. Action Over Words, Avoiding Over-communication

When encountering unexpected technical difficulties, climbers can easily fall into the trap of excessive shouting, which is often counterproductive and increases confusion.

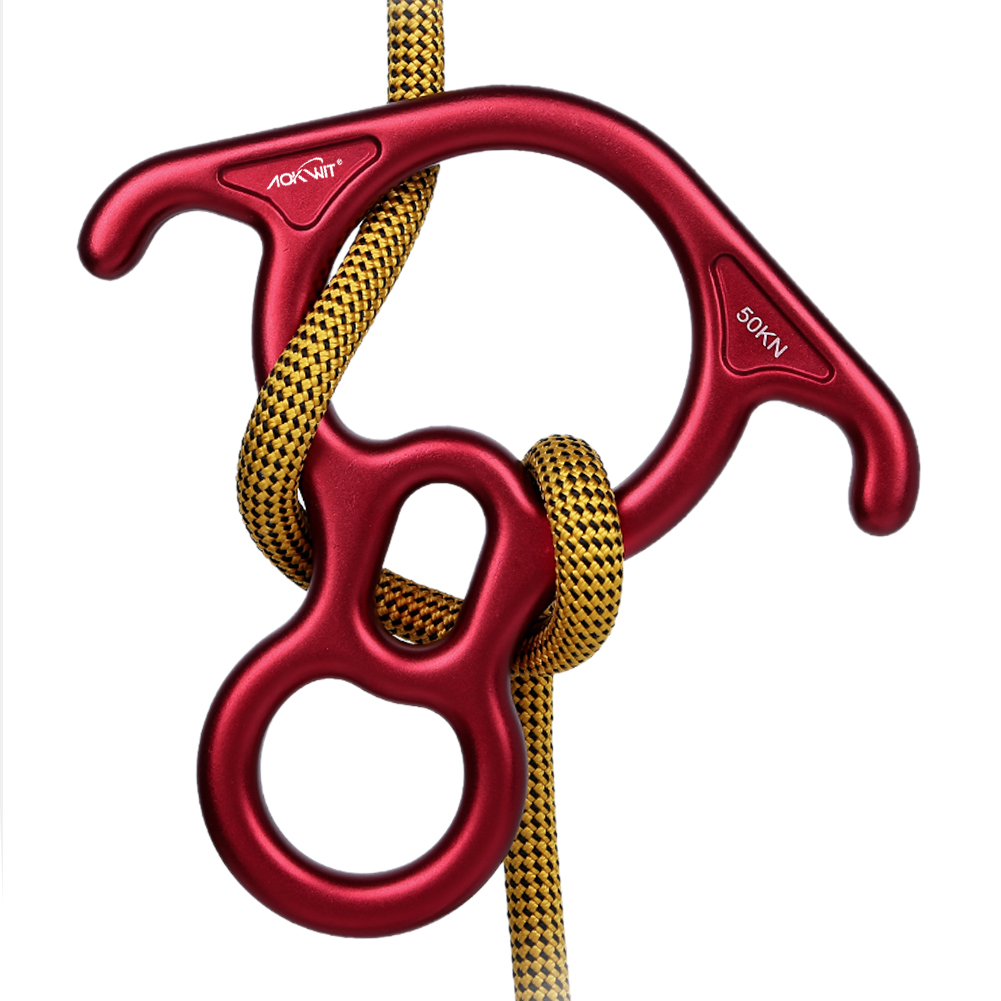

Independently Problem-Solve: For example, if gear becomes stuck, the climber should prioritize attempts to solve it independently using a nut tool or other equipment, rather than persistently trying to have a loud, hard-to-hear discussion with the partner.

Take Effective Action: For the belayer, if the follower below is in trouble, repositioning oneself to gain a clearer view or a more effective command angle is often more effective than simply shouting louder.

In some cases, lowering a panicked climber is a safer choice than forcing them to continue cleaning the route.

VIII. Developing Contingency Plans for Communication Failure

In situations where conventional verbal communication fails—such as due to strong wind, terrain blocking the line of sight—a thorough contingency plan can prevent tension and maintain control.

- Pre-establish Non-Verbal Signals: Standardize a system for conveying specific information through non-verbal means like rope tugs.

- Dynamic Strategy: The contingency plan should be flexible enough to handle combinations of multiple interfering factors.

For example, if facing strong wind, terrain blockage, and noise simultaneously, immediately switch to using radios. Simultaneously, a backup plan must be ready in case the radios are dead or malfunctioning.

IX. Conclusion

While rock climbing may be viewed as recreational in some contexts, its communication mechanisms concern safety and must never be taken lightly.

Clear, reliable, and concise communication is an indispensable cornerstone of climbing safety.

Regardless of a climber’s experience level or familiarity with their partner, communication must be prioritized, eliminating any complacency or reliance on luck.