Making Peace with Fear

Rock climbers are generally no strangers to fear.

Whether it’s the fear of falling or the fear of failure, this primal instinct is often awakened at some point.

Some climbers are naturally predisposed to lower levels of fear, while others avoid bouldering training due to an excessive fear of falling. These two extremes exist in reality:

Some climbers can easily handle 5.14 sport climbs, yet rarely make true first attempts due to a fear of falling, only bouldering in the gym as needed to maintain fitness.

Other climbers enjoy bouldering without protection, an experience akin to free soloing.

In recent years, the topic of fear has garnered increasing attention. Fear is not a zero-sum, either-or state; for most people, the practical path is learning to coexist with fear rather than completely conquering it.

Fear serves a protective function, enhancing safety awareness.

For instance, someone with a severe bee allergy understandably remains vigilant; there’s no need to eliminate that fear unless they choose to become a beekeeper.

For climbers, however, reducing the fear of falling, heights, or failure often yields greater benefits. Sometimes, instinct exaggerates risk, triggering fear and causing hesitation.

When trying highball bouldering or committing sport climbs, the sensation can be terrifying if one is unaccustomed to it.

Yet, with adequate crash pads and a reliable spotter, the actual risk is not increased—a fall might just be more uncomfortable.

True fearlessness, if not innate, is difficult to attain. Innate fearlessness means the brain is not prone to triggering a fear response under normal circumstances.

Nonetheless, it is possible to simulate a similar state through mental training.

“It’s possible to cultivate other psychological attributes so that fear recedes into the background.”

Fear still exists, but it no longer easily obstructs action.

There is no single type of training, medication, or ritual that can completely eliminate fear. The key lies in developing other psychological qualities, thereby reducing the propensity for fear to dominate.

Accumulating experience naturally diminishes fear, but this is not the only path; deeper layers remain worth exploring.

Reading this article won’t instantly dispel fear, nor does it provide specific steps or mantras to repeat.

Instead, it promotes an understanding of fear’s origins and the factors that intensify or alleviate it. The ultimate goal is to achieve reconciliation with fear, reducing the need for constant struggle against it.

Confidence

Fearlessness often stems from self-assurance.

When climbers are confident they possess the physical ability needed to complete a route, it becomes easier to overcome fear.

For example, in highball bouldering, if a climber can execute a difficult sequence at a low height, they should also be capable of doing so at a greater height.

The crucial factor is assessing the impact of accumulated fatigue: if the initial section of a route consumes significant energy, the likelihood of completing subsequent difficult moves decreases.

Clear self-awareness—including an understanding of the route’s structure, grade, and one’s own capabilities—forms the foundation for effective confidence.

Blind confidence, however, can lead to danger; therefore, confidence should be built upon solid ability and experience.

Trust

Trust in others is particularly important in climbing and can significantly alleviate fear.

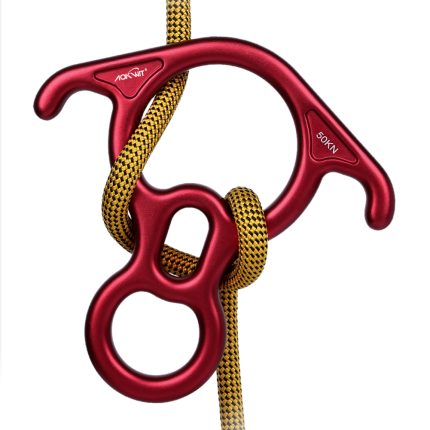

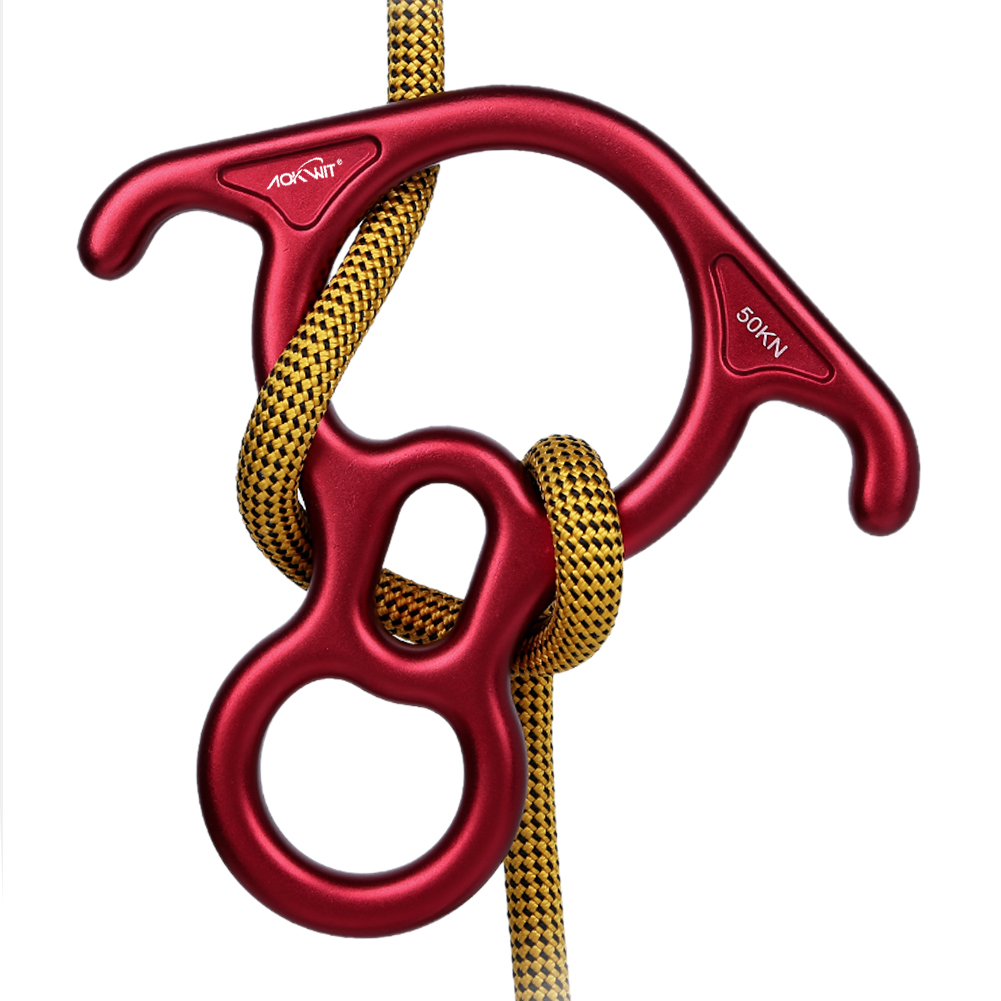

A reliable belayer and trustworthy equipment allow a climber to focus more on the climbing itself.

For instance, in a gym setting, climbers dare to attempt high-risk moves due to sufficient ground protection; outdoors, similar psychological security can be achieved if they trust their belay team.

Although some climbers, due to personal history, find it difficult to establish trust and instead compensate by strengthening their own control and ability, it is generally true that cultivating trust in a reliable environment is an effective way to mitigate fear.

Exposure

The classic method involves repeatedly exposing oneself to the fear-inducing situation, reducing the fear response through habituation.

This method applies to various scenarios: sport climbing, gear usage, taking whippers, and even enhancing the body’s adaptation and mobilization capabilities at a neurological level.

For example, regularly practicing falls while bouldering can help the body and mind adapt to the sensation of falling.

However, it’s important to note that environmental specificity is strong: practicing falls in a gym may not fully translate to outdoor scenarios with different rock types, angles, and protection conditions.

Therefore, targeted exposure—such as practicing falls on specific routes in real or simulated environments—is often more effective.

Consciously experiencing potential falls, like taking controlled practice whippers before a redpoint attempt, can significantly reduce fear during the actual climb.

Simultaneously, simulating the falling experience by jumping from appropriate heights onto pads also aids in mental preparation.

It’s important to balance the frequency of practice to avoid physical injury and to treat mental preparation as equally important as physical training.

Conclusion

Fear is not a dichotomous state.

By deeply understanding the roots of fear and accordingly adjusting climbing strategies and mental states, a balanced coexistence with fear can be achieved.

Fearlessness is not about fighting, controlling, or conquering fear, but about accepting it and learning to live with it.

The ideal process for managing fear might be linear: building trust → engaging with risk → accumulating experience → strengthening confidence → expanding the comfort zone.

In reality, however, each individual needs to find their own path based on their specific circumstances—such as propensity for trust, protection conditions, and confidence in ability.

Whether through strengthening ability to compensate for a lack of trust, or through gradual exposure to build confidence, the core objective is to reach a psychological reconciliation with fear.

This allows for progressing through one’s climbing career with greater composure and safety.