Grading of Climbing Route Difficulty

In some of our previously shared climbing stories, terms describing route grades such as 5.13b, 8a+, WI3, and M9 often appear. The following article focuses on how these difficulty grades are assessed, providing readers with a quick reference to identify differences between various levels.

Simply put, climbing grades describe the difficulty of the terrain on a route. These grades help climbers determine whether a route matches their skill level.

But what factors are considered in grading? Why are so many letters and numbers used? For ordinary readers, these technical terms seem daunting, and deciphering these abbreviations appears to be a challenging task. Let’s first understand the basic principles.

I. Who Sets the Grades?

Climbing grades are subjective, so difficulty is determined by consensus.

The first climber or team to complete a route has the first opportunity to assess its difficulty.

Thereafter, several other climbers (after completing the route) typically participate in the evaluation.

Finally, they reach a consensus on the route’s difficulty.

II. Glossary

- Route: The entire climbing path from the bottom to the top.

- Anchors: Any device (such as bolts or pitons) that connects the rope or climber to the climbing surface.

- Pitch: The distance between two anchors on a route, longer than the rope. For example, a standard 70-meter rope can be used to climb a 200-meter route in 3 pitches.

- Free Climbing: Also known as freehand climbing, it means ascending using only one’s hands, feet, and the natural features of the rock.

- Aid Climbing: Using devices fixed on the rock not only for protection but also for upward progress during climbing.

III. Climbing Rating Systems

The two most commonly used climbing rating systems are the French Numerical System (FR) and the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS).

1. French Numerical System (FR) – e.g., 6a, 8b+

The French Numerical System is the primary rating system for free climbing outside North America (abbreviated as FR below).

FR evaluates climbing levels based on the overall technical difficulty and intensity of the route.

Ratings start at 1 (indicating very easy) and have no upper limit.

Grades at level 5 and above can be further distinguished by adding lowercase letters a, b, or c.

Additionally, a “+” can be added to indicate more sustained difficulty (6a+ is harder than 6a but easier than 6b).

Currently, the world’s most difficult route grade is 9c.

2. Yosemite Decimal System (YDS) – e.g., 5.6, 5.11a

YDS is the primary rating system in the United States and parts of Canada.

Developed by the U.S.-based Sierra Club in the 1950s, YDS unified and refined the early climbing systems in Yosemite Valley. YDS classifies technical difficulty into five categories:

- Classes 1 & 2: Related to hiking and trail running.

- Classes 3 & 4: Refer to easily climbable slightly inclined terrain.

- Class 5: Describes technical climbing.

Class 5 ratings start at 5.0, representing a low-angle slope requiring minimal skills.

5.15 is currently the most difficult grade.

The official description of 5.15 terrain is: “Extremely difficult, typically involving cliff faces or overhangs, requiring excellent expertise, physical conditioning, and technical proficiency.”

Only exceptional climbers can handle 5.15 difficulty.

For slopes rated above 5.10, letters a to d may also be added during rating.

For example, a route or rock slope rated 5.10a is easier than one rated 5.10b.

5.13 is harder than 5.12d but easier than 5.13a, and so on.

Note: A route’s technical difficulty does not determine the objective risk for climbers.

Risk depends on various factors, including the quality of climbing hardware, rock conditions, and runout (the distance between anchors or gear placements).

IV. NCCS Time Grades

In the United States, there is also a system for measuring the “time” required for a route. The National Climbing Classification System (NCCS) time grades rate routes based on the average time a team spends on them:

- Class I: 1–3 hours

- Class II: 3–4 hours

- Class III: 4–6 hours

- Class IV: A full day of climbing, typically with minimal technical difficulty (usually 8–12 hours)

- Class V: Requires an overnight stay

- Class VI: Lasts more than two days and up to one week

- Class VII: Long and significant big-wall expeditions, usually in remote areas, lasting one week or more

V. Other Rating Systems

Free climbing is not the only form of climbing with difficulty ratings. Ice climbing and mixed climbing also require grading systems, which we briefly introduce below.

1. Ice Climbing Grades – e.g., WI3+, WI6

- WI1: Low-angle ice; no tools needed.

- WI2: Smooth 60° ice, possibly with small bulges; good protection.

- WI3: Sustained 70° ice, possibly with large 80°–90° bulges; reasonable rests and good positions for placing ice screws.

- WI4: Continuous 80° ice with significant sections of 90° ice protrusions.

- WI5: Long and strenuous, on short, thin ice at 85°–90°, with short pitches, few rest spots, and difficult protection placement.

- WI6: A full rope length of nearly 90° ice, with no rests or shorter pitches, more strenuous than WI5, and highly technical.

- WI7: As above, but on thin, poorly bonded ice or long, overhanging, poorly bonded icicles. Protection is impossible or difficult, and the ice is unpredictable.

- WI8 and above: Equivalent to bouldering on rope using ice tools and crampons, usually with bolts for protection.

2. Mixed Climbing Grades – e.g., M1, M8

Mixed terrain grades range from M1 (low-angle terrain, usually requiring no ice tools) to M12 (steep terrain with gymnastic moves on fragile holds). Grades M13–16 are generally considered speculative.

- M1–3: Simple low-angle terrain, usually no tools needed.

- M4: From slab to vertical terrain, requiring some technical dry tooling.

- M5: Some sustained vertical dry tooling.

- M6: Vertical to overhanging routes, high-difficulty dry tooling.

- M7: Overhanging; powerful technical dry tooling, with the difficult section less than 10 meters long.

- M8: Some nearly horizontal overhanging terrain, requiring very powerful technical dry tooling, bouldering, or longer difficult sections than M7.

- M9: Can be continuously vertical or slightly overhanging edges or technical points, or horizontal rock roofs, with space for placing multiple tools over 2–3 body lengths.

- M10: At least 10 meters of horizontal rock or 30 meters of overhanging dry tooling, with smooth and powerful moves and no rests.

- M11: A rope-length overhanging gymnastic climb or a rock roof up to 15 meters high.

- M12: M11-level bouldering with dynamic moves and fragile technical holds.

- M13–M16: Speculative. The world’s most difficult mixed routes, such as those discovered by Will Gadd and others at Helmcken Falls, British Columbia, Canada, do not distinguish grades above M13.

VI. Rating Applications

In our climbing stories, you will never see French numerical grades below 1 (5.0 YDS), as these represent very easy climbs.

You may see 6b+ (5.10d YDS), meaning the climb is above intermediate level and within the capability of an experienced, physically fit climber with technical knowledge.

8a (5.13a YDS) and above are considered advanced climbing, with 9a (5.14d YDS) being the international standard for excellent free climbing. Many Olympic-level climbers can handle 9a or harder routes, but this is rare for non-professional climbers.

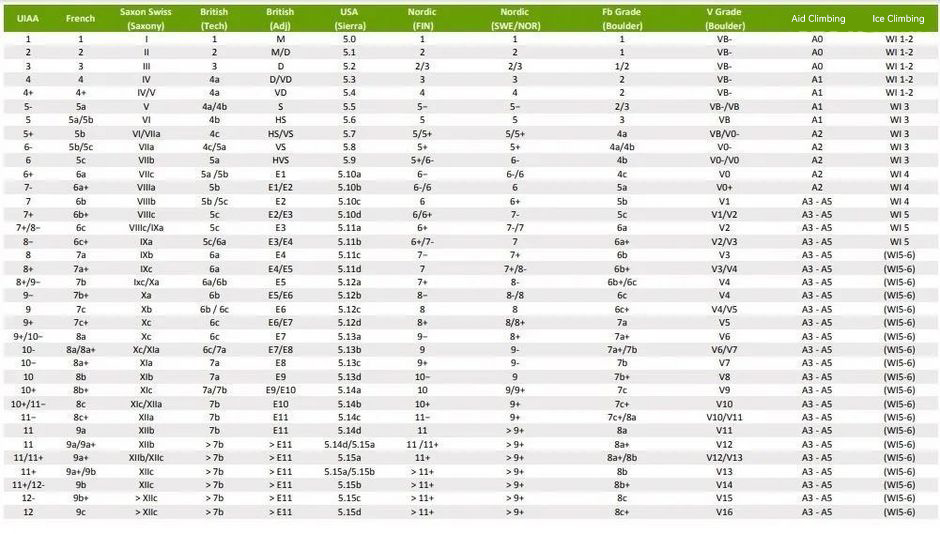

VII. Conversion Table

Need to know how FR ratings convert to YDS? Below is a comprehensive conversion table for the 10 most common rating systems.

(Note: “French” in the table refers to the French Numerical System, and “USA (Sierra)” refers to the Yosemite Decimal System.)